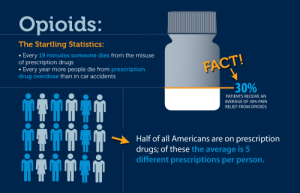

When you experience a mild headache or chronic pain , an over-the-counter pain reliever is typically sufficient to provide relief. However, in cases of more severe pain, your physician may suggest a stronger option: a prescription opioid.

Opioids belong to the category of narcotic pain medications and can pose significant risks if not used properly. It’s worth noting that for individuals who develop an opioid addiction, it often begins with a legitimate prescription.

If you require opioids to manage your pain, here are some guidelines to ensure you are using them as safely as possible.

How Do Opioids Work?

Opioid drugs bind to opioid receptors in the brain, spinal cord, and other areas of the body. They tell your brain you’re not in pain.

They are used to treat moderate to severe pain that may not respond well to other pain medications.

Opioids work by interacting with specific receptors in the brain, spinal cord, and throughout the body’s central nervous system. These receptors are known as opioid receptors, and there are three primary types: mu, delta, and kappa receptors. Opioids primarily bind to mu receptors, which play a central role in pain relief and the side effects associated with opioid use.

Here’s how opioids work to relieve pain and produce other effects:

- Pain Relief: Opioids reduce the perception of pain by binding to mu receptors in the brain and spinal cord. When opioids bind to these receptors, they inhibit the transmission of pain signals and alter how the brain perceives pain. This can provide significant pain relief, making opioids effective for moderate to severe pain management.

- Euphoria and Sedation: Opioid use can lead to feelings of euphoria and relaxation. These effects are also mediated by the activation of mu receptors, which can produce a sense of well-being and tranquility.

- Respiratory Depression: One of the side effects of opioids is the slowing down of breathing, known as respiratory depression. This occurs because opioid receptors are also present in the brainstem, where respiratory control centers are located. High doses of opioids can lead to severe respiratory depression, which is a life-threatening condition.

- Gastrointestinal Effects: Opioids can cause constipation by affecting the gastrointestinal tract. This occurs because opioids slow down the movement of the digestive system.

- Tolerance and Dependence: Over time, the body can develop tolerance to opioids, requiring higher doses to achieve the same level of pain relief. Additionally, chronic opioid use can lead to physical dependence, meaning the body becomes accustomed to the presence of the drug, and withdrawal symptoms occur when the drug is discontinued.

It’s important to note that the same mechanisms that make opioids effective for pain relief can also lead to their potential for misuse, addiction, and adverse side effects. Proper medical supervision and adherence to prescribed dosages are critical when using opioid medications to manage pain.

How many Opioids Are There ?

There are many different opioids available for medical use, and they come in various forms and formulations. here are twenty opioid medications with a brief description of each:

- Morphine: A potent opioid often used for severe pain management, such as post-surgery or cancer-related pain. It’s available in various forms, including oral and injectable.

- Oxycodone: A commonly prescribed opioid for moderate to severe pain. It comes in immediate-release and extended-release formulations. Medications like Percocet contain oxycodone.

- Hydrocodone: Frequently used in combination with other medications, such as acetaminophen, in drugs like Vicodin. It’s prescribed for pain relief, especially after dental procedures.

- Codeine: A less potent opioid used for mild to moderate pain and as a cough suppressant. It’s often found in prescription and over-the-counter medications.

- Fentanyl: A highly potent synthetic opioid used in medical settings for severe pain management. It’s available in various forms, including patches and lozenges.

- Tramadol: A synthetic opioid used for moderate pain. It’s considered to have a lower risk of dependence compared to stronger opioids.

- Hydromorphone: A potent opioid used for the management of severe pain. It’s available in various forms, including oral and injectable.

- Buprenorphine: Used not only for pain relief but also in medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction. It has a lower risk of respiratory depression.

- Methadone: Used in the treatment of opioid addiction and, less commonly, for pain management. It has a long duration of action and is used in opioid maintenance therapy.

- Meperidine (Demerol): A synthetic opioid used for pain relief, particularly in labor and delivery. It has a shorter duration of action than some other opioids.

- Tapentadol: An opioid used for moderate to severe pain. It’s considered to have a lower risk of gastrointestinal side effects compared to other opioids.

- Butorphanol: A synthetic opioid used for pain relief and as an analgesic during labor and delivery.

- Nalbuphine: An opioid with mixed agonist-antagonist properties used for pain management, particularly after surgery.

- Levorphanol: A synthetic opioid used for pain relief, particularly in cases where other opioids are ineffective.

- Oxymorphone: A potent opioid used for severe pain, often in extended-release formulations.

- Pentazocine: A mixed agonist-antagonist opioid used for moderate to severe pain, especially after surgery.

- Dihydrocodeine: A semi-synthetic opioid used for pain relief, particularly in combination with other medications.

- Remifentanil: An ultra-short-acting synthetic opioid used in anesthesia for pain control during surgical procedures.

- Sufentanil: An extremely potent synthetic opioid often used in anesthesia and for pain control in critical care settings.

- Etorphine: A powerful veterinary opioid used for immobilizing large animals. It is not used in human medicine.

Please note that these opioids vary in potency, duration of action, and specific medical applications. They should be used only as prescribed by a healthcare professional and with careful consideration of individual patient needs and risks.

What Are the Side Effects of Opioids?

Opioids, when used for pain relief, can have various side effects. These side effects may vary from person to person and depend on the specific opioid medication, dosage, and individual factors. Common side effects of opioids include:

- Drowsiness and Sedation: Opioids can cause drowsiness, making it difficult to concentrate or stay awake.

- Constipation: Opioids often lead to constipation, which can become a chronic issue with long-term use.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Some individuals may experience nausea and vomiting when taking opioids.

- Dizziness: Opioids can cause a feeling of lightheadedness or dizziness.

- Itching: Opioid use may lead to itching or skin reactions in some people.

- Respiratory Depression: This is a serious side effect that can slow down breathing. It’s more common with high doses of opioids.

- Tolerance: Over time, the body may become tolerant to opioids, requiring higher doses for the same pain relief.

- Dependence and Addiction: Opioids have a potential for dependence and addiction, especially when used improperly or for extended periods. This can lead to withdrawal symptoms when trying to stop using them.

- Hormonal Imbalances: Chronic opioid use can disrupt the endocrine system and lead to hormonal imbalances.

- Sleep Disturbances: Opioids can affect sleep patterns, leading to problems with insomnia.

- Cognitive Impairment: Some individuals may experience cognitive impairment, affecting memory and mental clarity.

- Mood Changes: Opioids can impact mood, leading to symptoms of depression or anxiety.

It’s essential to use opioids only as prescribed by a healthcare professional and to closely monitor their effects. Additionally, individuals should be aware of the potential for dependence and addiction and use opioids with caution, especially for long-term pain management.

The primary method for addressing moderate to severe pain linked to cancer or other severe medical conditions is through the use of opioid therapy.

The Primary Use of Opioid Therapy is For Cancer or Severe Medical Conditions

Opioid therapy is the mainstay approach for the treatment of moderate to severe pain associated with cancer or other serious medical illnesses (Patt & Burton, 1998; World Health Organization, 1996). Although the use of opioid analgesics for the treatment of CNMP has been increasing in recent years (Joranson, Ryan, Gilson & Dahl, 2000) and has been endorsed by numerous professional societies (AAPM, APS, 1997; American Geriatric Society, 1998; Pain Society, 2004), the use of opioids remains controversial due to concerns about side effects, long-term efficacy, functional outcomes, and the potential for drug abuse and addiction. The latter concerns are especially evident in the treatment of CNMP patients with substance use histories (Savage, 2003).

Other concerns that may contribute to the hesitancy to prescribe opioids may be related to perceived and real risks associated with regulatory and legal scrutiny during the prescribing of controlled substances (Office of Quality Performance, 2003). These concerns have propelled extensive work to develop predictors of problematic behaviors or frank substance abuse or addiction during opioid therapy. Questionnaires to assist in this prediction and monitoring have been developed and used in research and field trials. Examples include the Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ; Compton et al., 1998); the Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool (PADT; Passik et al., 2004) and the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM; Butler et al., 2007). These instruments are not used in practice settings at this time.

Narrative reports on the use of opioids for CNMP have underscored the effectiveness of opioid therapy for selected populations of patients and there continues to be a consensus among pain specialists that some patients with CNMP can benefit greatly from long-term therapy (Ballantyne & Mao, 2003; Trescot et al., 2006). This consensus, however, has received little support in the literature. Systematic reviews on the use of opioids for diverse CNMP disorders report only modest evidence for the efficacy of this treatment (Trescot et al., 2006; 2008). For example, a review of 15 double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trials reported a mean decrease in pain intensity of approximately 30% and a drop-out rate of 56% only three of eight studies that assessed functional disturbance found improvement (Kalso, Edwards, Moore, & McQuay, 2004).

A meta-analysis of 41 randomized trials involving 6,019 patients found reductions in pain severity and improvement in functional outcomes when opioids were compared with placebo (Furlan, Sandoval, Mailis-Gagnon, & Tunks, 2006). Among the 8 studies that compared opioids with non-opioid pain medication, the six studies that included so-called “weak” opioids (e.g., codeine, tramadol) did not demonstrate efficacy, while the two that included the so-called “strong” opioids (morphine, oxycodone) were associated with significant decreases in pain severity. The standardized mean difference (SMD) between opioid and comparison groups, although statistically significant, tended to be stronger when opioids were compared with placebo (SMD = 0.60) than when strong opioids where compared with non-opioid pain medications (SMD = 0.31). Other reviews have also found favorable evidence that opioid treatment for CNMP leads to reductions in pain severity, although evidence for increase in function is absent or less robust (Chou, Clark, & Helfand, 2003; Eisenberg, McNicol, & Carr, 2005).

Little or no support for the efficacy of opioid treatment was reported in two systematic reviews of chronic back pain (Deshpande, Furlan, Mailis-Gagnon, Atlas, & Turk, 2007; Martell, et al., 2007). Because patients with a history of substance abuse typically are excluded from these studies, they provide no guidance whatsoever about the effectiveness of opioids in these populations.

Adding further to the controversy over the utility of opioid analgesics for CNMP is the absence of epidemiological evidence that an increase in the medical use of opioids has resulted in a lower prevalence of chronic pain. Noteworthy is a Danish study of a national random sample of 10,066 respondents (Eriksen, Sjøgren, Bruera, Ekholm, & Rasmussen, 2006).

Denmark is known for having an extremely high national usage of opioids for CNMP and this use has increased by more than 600% during the past two decades (Eriksen, 2004). Among respondents reporting pain (1,906), 90% of opioid users reported moderate to very severe pain, compared with 46% of non-opioid users; opioid use was also associated with poor quality of life and functional disturbance (e.g., unemployment).

Although this epidemiological study may be interpreted as demonstrating that opioid treatment for CNMP has little benefit, the authors acknowledge that these disquieting findings do not indicate causality and could be influenced by the possibility of widespread undertreatment, leading to poorly managed pain.

This latter interpretation is supported by a commentary on the Ericksen et al. study (Keane, 2007). Keane notes that among the 228 pain patients receiving opioids only 57 (25%) were using strong opioids, while the remainder was using weak opioids. European (as well as United States) clinical guidelines generally recommend long-acting formulations of strong opioids for the treatment of chronic moderate to severe pain, which may be supplemented with short-acting opioids for breakthrough pain (Pain Society, 2004; OQP, 2003; Gourlay, 1998; Vallerand, 2003; Fine & Portenoy, 2007).

The possibility of inappropriate opioid treatment is further supported by another Danish study that assigned pain patients who were on opioid therapy to either a multidisciplinary pain center (MPC) or to general practitioners (GP) who had received initial supervision from the MPC staff (Eriksen, Becker, & Sjegren, 2002). At intake, a substantial number of patients in both groups were apparently receiving inappropriate opioid therapy for chronic pain (60% were being treated with short-acting opioids and 49% were taking opioids on demand). At the 12 month follow-up, 86% of MPC patients were receiving long-acting opioids and 11% took opioids on demand.

There was no change in the administration pattern in the GP group. These findings suggest that a significant proportion of opioid-treated CNMP patients may be receiving inappropriate opioid treatment and that educating general practitioners in pain medicine may require more than initial supervision.

It is generally acknowledged that there is a wide degree of variance in the prescribing patterns of opioids for chronic pain (Lin, Alfandre, & Moore, 2007; Trescot et al., 2006). Some opioid treatment practices persist despite evidence that they might be harmful or have little benefit, such as the over-prescribing of propoxyphene among the elderly (Barkin, Barkin, & Barkin, 2006; Singh, Sleeper, & Seifert, 2007). Nursing home patients being treated with opioids have been found to be inadequately assessed for pain and to be more likely treated with short-acting rather than long acting opioids (Fujimoto & Coluzzi, 2000). A substantial number of physicians are reluctant or unwilling to prescribe long-acting opioids to treat CNMP, even when it may be medically appropriate (Nwokeji, et al., 2007).

Controversy about the long-term effectiveness of opioid treatment also has focused on the potential clinical implications of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. As noted earlier, exposure to opioids can result in an increased sensitivity to noxious stimuli in animals, and an increased perception of some types of experimental pain in humans (c.f., Koppert & Schmeltz, 2007; Angst & Clark, 2006). Anecdotal reports of hyperalgesia occurring with very high or escalating doses of opioids (Angst & Clark, 2006) has been viewed as a clinical correlate of these experimental findings.

The extent to which this phenomenon is relevant to the long-term opioid therapy administered to most patients with chronic pain is unknown. Although experimental evidence suggests that opioid-induced hyperalgesia might limit the clinical utility of opioids in controlling chronic pain (Chu, Clark, & Angst., 2006), there have been no reports of observations in the clinical literature to suggest that it should be a prominent problem. More research is needed to determine whether the physiology underlying opioid-induced hyperalgesia may be involved in a subgroup of patients who develop problems during therapy, such as loss of efficacy (tolerance) or progressive pain in the absence of a well defined lesion.

Outcome studies of long term use of opioids are compromised by methodological limitations which make it difficult to acquire evidence of efficacy (Noble, Tregear, Treadwell, & Schoelles, 2007). Methodological limitations may be unavoidable because of the ethical and practical challenges associated rigorous studies such as randomized controlled trials. Guidelines for opioid therapy must now be based on limited evidence; future evidence may be acquired by utilizing other study designs (Noble et al., 2007) such as practical clinical trials (Tunis, Stryer, & Clancy, 2003). These studies should include at least three criteria to reflect a positive treatment response: i.e., reduction of pain severity (derived from subjective reports or scores on pain scales), recovery of function (improved scores on instruments that measure some aspect of function), and quality of life.

Guidelines for the use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain have been published (AAFP et al., 1996–2002; OQP, 2003), and recent guidelines have emphasized the need to initiate, structure and monitor therapy in a manner that both optimizes the positive outcomes of opioid therapy (analgesia and functional restoration) and minimize the risks associated with abuse, addiction and diversion (Portenoy et al., 2004). These guidelines discuss patient selection (highlighting the likelihood of increased risk among patients with prior histories of substance use disorders), the structuring of therapy to provide an appropriate level of monitoring and a presumably lessened risk of aberrant drug-related behavior, the ongoing assessment of drug-related behaviors and the need to reassess and diagnose should these occur, and strategies that might be employed in restructuring therapy should aberrant behaviors occur and the clinician decide to continue treatment.

They also note that therapy should be undertaken initially as a trial, which could lead to the decision to forego more therapy, and that an “exit strategy” must be understood to exist should the benefits in the individual be outweighed by the burdens of treatment.

The relatively recent recognition that guidelines for the opioid treatment of chronic pain must incorporate both the principles of prescribing as well as approaches to risk assessment and management may represent an important turning point for this approach to pain management. Acknowledging that prescription drug abuse has increased during the past decade, a period during which the use of opioid therapy by primary care physicians and pain specialists has accelerated, pain specialists and addiction medicine specialists now must collaborate to refine guidelines, help physicians identify the subpopulations that can be managed by primary care providers, and discover safer strategies that may yield treatment opportunities to larger numbers of patients.

Opioid Tolerance and Addiction

Tolerance and addiction are two significant concerns associated with opioid use:

- Tolerance: Tolerance refers to the body’s reduced response to a drug over time. With opioids, it means that as you use them regularly, you may need higher doses to achieve the same level of pain relief. This can be a natural physiological response to the medication.

- Addiction: Addiction is a complex condition characterized by a compulsive and uncontrollable craving for a substance, despite harmful consequences. Opioid addiction can result from both prescription and non-prescription opioid use. It often involves a psychological and physical dependence on the drug, and individuals may engage in drug-seeking behaviors.

It’s essential to use opioids under the guidance of a healthcare professional and as prescribed. Tolerance does not necessarily indicate addiction, but it can increase the risk of developing an addiction. It’s crucial to be aware of the signs of addiction, such as loss of control over opioid use, cravings, and adverse life consequences, and seek help if addiction is suspected.

Should You Take Opioid Pain Medications?

The decision to take opioid pain medications should be made in consultation with a healthcare professional. Opioid pain medications can be effective for managing certain types of pain, especially in cases of moderate to severe pain caused by conditions like cancer, surgery, or serious injuries. However, they come with risks and should be used judiciously.

Here are some considerations when deciding whether to take opioid pain medications:

- Medical Evaluation: Your healthcare provider will assess your pain and medical condition to determine if opioids are an appropriate treatment option.

- Risk vs. Benefit: Consider the potential benefits of pain relief against the risks associated with opioid use, including side effects, tolerance, and addiction.

- Alternative Treatments: Explore non-opioid pain management strategies, such as physical therapy, non-prescription pain relievers, or nerve blocks, which may be effective for your condition.

- Discussion: Have an open and honest discussion with your healthcare provider about your pain, treatment options, and any concerns you may have.

- Prescription Guidelines: If your healthcare provider prescribes opioids, make sure to follow the prescription instructions precisely. Do not increase the dose or frequency without consulting your healthcare provider.

- Monitoring: Regularly communicate with your healthcare provider about the effectiveness of the medication, any side effects, or concerns about tolerance or addiction.

- Risk Factors: Be aware of personal risk factors for opioid addiction, such as a history of substance abuse or mental health issues.

- Exit Strategy: Discuss a plan with your healthcare provider for tapering off opioids when they are no longer needed to manage your pain.

Opioid medications can be a valuable tool for pain management in certain situations, but they should be used responsibly and under close medical supervision. It’s important to balance the benefits of pain relief with the potential risks and explore alternative treatments when appropriate.

When do You ask the Doctors to Prescribe you Opioids ?

You should ask a doctor to prescribe opioids when you are experiencing moderate to severe pain, and other non-opioid pain relief methods have proven to be ineffective or insufficient in managing your pain. It’s essential to have an open and honest discussion with your healthcare provider about your pain and treatment options. Here are some general guidelines for when to consider asking for an opioid prescription:

- Severe Pain: Opioids are typically prescribed for cases of severe pain, such as post-surgery pain, cancer-related pain, or severe injuries. If your pain is significantly affecting your quality of life and daily functioning, it may be appropriate to discuss the use of opioids.

- Chronic Pain: In some situations, chronic pain conditions that significantly impact your daily life may warrant the use of opioids. However, this decision should be carefully considered, and non-opioid treatments should be explored first.

- Non-Responsiveness: If other pain management methods, such as over-the-counter pain relievers, physical therapy, or non-opioid medications, are not effectively controlling your pain, it may be time to discuss opioid therapy with your healthcare provider.

- After Surgery: Opioids are commonly prescribed for post-surgery pain management. In this case, your doctor will determine the appropriate opioid and dosage based on the type and extent of the surgery.

- Cancer Pain: Cancer-related pain can be excruciating, and opioids are often used to provide relief. In these cases, pain management is an essential part of cancer care.

It’s crucial to remember that opioid medications should be used judiciously, under the guidance of a healthcare professional, and according to the prescribed dosage and schedule. Additionally, potential risks and side effects of opioids, including the risk of tolerance and addiction, should be discussed with your doctor. If opioids are prescribed, close monitoring of their use and regular communication with your healthcare provider are essential to ensure safe and effective pain management.

Can I Buy Opioids Online ?

The sale and distribution of opioids without a valid prescription from a licensed healthcare provider is illegal and dangerous. It’s important to prioritize your health and well-being and seek medical advice from a healthcare professional if you are dealing with pain or health-related issues. Do not attempt to purchase or use opioids without a legitimate prescription and proper medical supervision, as doing so can lead to serious health risks and legal consequences.

Pain Medications, Pain Relief, and Pain Management